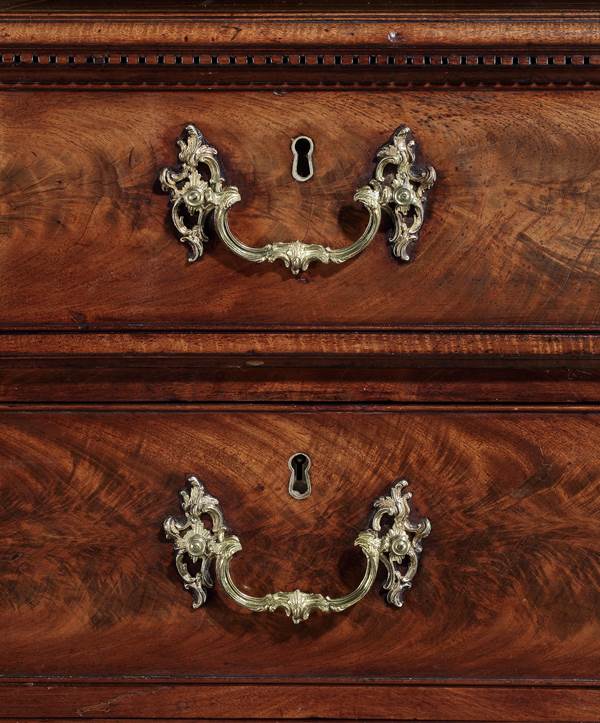

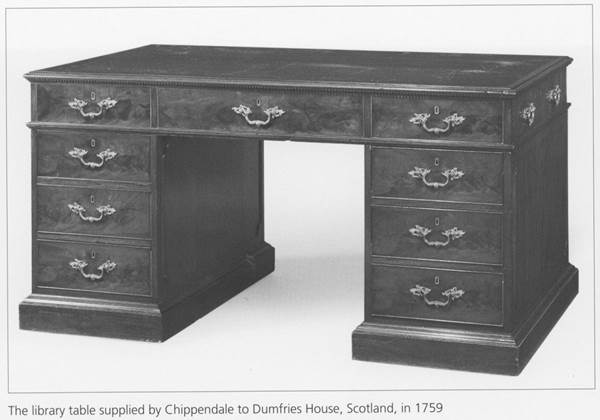

The desk retains virtually all the original ornate brass handles to the drawers, which are identical to the ones used by the Chippendale firm on the library table supplied to Dumfries House, Scotland, in 1759. The false drawers in the frieze on the front and reverse side conceal large side drawers. The reverse side of each pedestal is fitted with single doors, with two fixed shelves behind each door.

Note: The leather insert to the top is a replacement. One side drawer is fitted with a double rising writing slope which is a faithful restoration, copying the Dumfries library table. The castors to the underside of each pedestal are 19th century replacements. Victorian lifting handles, one on each side of the table, have been removed.

The desk is identical in almost every detail to the Dumfries library table. There are, however, two variations from the Dumfries model. Firstly, the reverse side of each pedestal on this desk is fitted with two fixed shelves behind the door, whilst the Dumfries desk has folio divisions in their place. Secondly, the two desks use slightly different types of mahogany. The Dumfries desk is constructed of fine mahogany and veneered with fine crutch veneers. This desk is constructed of slightly better fiddle back mahogany, and slightly finer crutch veneers.

The Chippendale Dumfries account for the library table, dated 5 May 1759, reads: ‘a Mahogany Library-Table of very fine wood the top cover’d wt. best black leather, a Writing drawer at one End wt. a double rising slider cover’d, & drawers & Cupboards in the sides & strong triple wheel castors £22 - - .’

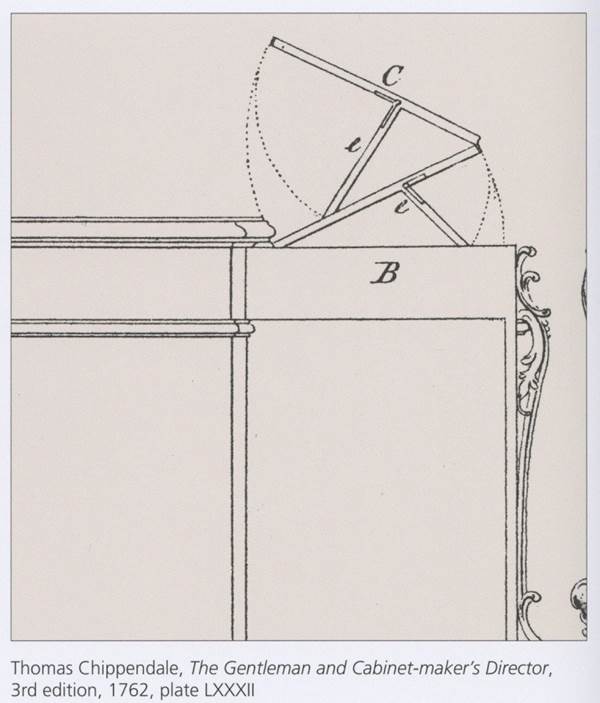

The design for the library table is based on plate LIV in the first edition and plate LXXIX in the third edition of Chippendale’s Director. A drawing for the double rising reading rest in the side drawer appears only in the third edition, in plate LXXXII: we know, however, that the Dumfries desk was delivered three years before the third edition appeared, and can therefore assume that this design, though not yet published, had already been realised some time earlier.

There are twelve known commissions for various models of library tables by the firm, and prices range from £12 for a library table installed at Mersham-le-Hatch, Kent, England, to £36 for a table with carved ornament for Aske Hall, Yorkshire, England. Sadly, no bill has survived for the celebrated library table made for Harewood House, also in Yorkshire, which is veneered in fine marquetry and mounted with finely chased brasses, but it is certain that the cost would have exceeded that of all the other library tables made in the Chippendale workshop.

Lord Dumfries visited London in January 1759 to order the first batch of furniture, including the library table, and it was invoiced in May the same year. The relatively short period between the order being placed and the bulk of furniture being delivered suggests that some pieces were ready-made stock items that could be dispatched at short notice. The possibility that the library table falls into this category is supported by a virtually identical example having come to light.

Further research may one day reveal the house this library table was made for. The lack of batten holes and marks of transport fixings suggests that the table did not have to travel far and was therefore perhaps made for a London house.

A library table fitting the description of this library table was supplied on 23 June 1766 to Sir Rowland Winn at his London address, 11 St. James’s Square:

To a very large mahogany Library Table covered with black leather and a writing drawer double spring and tumbler locks to ditto, covered with green cloth. £12

The Winn family gave up the London house following Sir Rowland’s death in 1785, and its furniture was either sold at auction or brought back to Nostell Priory, Yorkshire. The library table recorded in the 1766 invoice is not at Nostell, but the Christie’s auction catalogue of April 1785 for 11 St. James’s Square lists it as being in the study there:

No. XIV The Study

Lot 2. A large mahogany library table with drawers on each side, top covered with black leather.

The library table was sold to ‘MG’ for £6 6s. Unfortunately we do not know who MG was, which for the time being brings the research to an end, but it is possible that this library table came from Sir Rowland Winn’s town house.

Literature:

Thomas Chippendale, The Gentleman and Cabinet-maker’s Director, 1754, pl. LIV.

Thomas Chippendale, The Gentleman and Cabinet-maker’s Director, 3rd edition, 1762, pls LXXIX & LXXXII.

Christopher Gilbert, The Life and Work of Thomas Chippendale, 1978, vol. I, pp. 133 & 138, figs. 43–2.

Christie, Manson & Woods, ‘Dumfries House – A Chippendale Commission’, sale catalogue, 12–13 July 2007, vol. I, pp. 124–9, lot 30.

Looking for something similar? YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

YOU HAVE RECENTLY VIEWED ITEMS

Make an enquiry

- CAN WE HELP YOU?

- +44 (0)20 7493 2341

- [email protected]