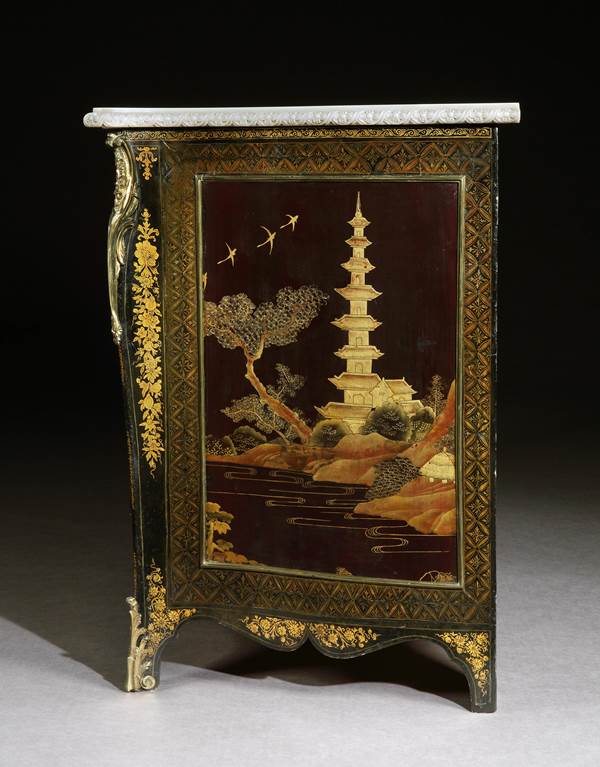

A pair of George II ormolu mounted Chinese lacquer commodes attributed to Pierre Langlois.

Note: The commodes retain the original jasper and statuary marble tops, each with finely carved guilloche edges, and the original ormolu mounts. The interior of each commode is fitted a single shelf.

THE ATTRIBUTION TO LANGLOIS

Pierre Langlois established himself as one of the leading London cabinet-makers in the 1760s and 1770s, producing furniture in the French taste. His use of marquetry and brass mounts is comparable to that of the German-born Paris ébéniste Jean-François Oeben, with whom Langlois probably trained.

The use of Chinese lacquer limits the cabinet-maker to two-dimensional serpentine shapes only, as lacquer will not bend in two directions to form bombé shapes. In London, Langlois produced commodes mostly in the bombé form, curved in three dimensions and veneered with exotic woods, but also some serpentine models veneered with lacquer.

Similar commodes attributed to the Langlois workshop include examples at Uppark, West Sussex, England, which originally had two pairs, of which one remains at the house; a commode formerly at Ragley Hall, Warwickshire, England; a commode at Polesden Lacey, Surrey, England; and another formerly in the collection of Lady Agnes Peel.

THE CHINESE LACQUER

The vogue for exotic lacquer surfaces on furniture made in England in the mid 18th century led to cabinet-makers removing the lacquer decoration from export pieces from Japan and China, such as chests, coffers and screens. The lacquer was generally re-used in ways that took the original decoration into account, but in some cases the decoration played no part in the design of the new piece. One example of the latter is the well-documented Japanese lacquer mirror from Althorp, Northamptonshire, England, now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, England, where the lacquer panels are used with the original pattern appearing upside down and sideways.

The lacquer on the Ashburnham commodes forms a continuous picture across the doors on each commode. These lacquer panels are framed by japanned decoration in geometrical patterns. The leg trusses and the aprons are decorated with floral husks and are also japanned. Japanning is the European imitation of Oriental lacquer.

The size and type of decoration of the lacquer panels suggest that they were cut from larger vertical panels such as the ones used on folding screens. These screens were supplied to England from the 17th century onwards and were often repurposed in this way.

Interestingly, the lacquer used on the Uppark commodes shares many characteristics with the lacquer used on the Ashburnham commodes, and it is entirely possible that the lacquer in both groups is from the same folding lacquer screen.

THE ORMOLU MOUNTS

Pierre Langlois shared his workshops at 39 Tottenham Court Road, London, with his son-in-law, the metal founder and gilder Dominique Jean. It is more than likely that the angle mounts on these commodes were produced by Jean.

THE VENEERED JASPER AND WHITE MARBLE TOPS

Langlois may have worked with Thomas and Benjamin Carter, who supplied marble tops for commodes at Strawberry Hill, Twickenham, London. At Ashburnham, a Benjamin Carter also supplied a carved marble chimneypiece, and it is possible that these tops were also supplied by the Carter family.

ASHBURNHAM PLACE

John, 2nd Earl Ashburnham became Lord of the Bedchamber in 1748, in the inner circle of the King’s courtiers. In 1765 he was appointed Master of the Great Wardrobe and in 1775 Groom of the Stole. Other positions held by him were the Keeper of Hyde Park and St. James’s Park, Lord Lieutenant of Sussex and Vice Admiral of Sussex. Ashburnham’s many honorary titles paint a picture of a man of the utmost importance to the King and his Government.

His position and ancestral wealth allowed him to set out and furnish Ashburnham Place, Sussex, and Ashburnham House, his London residence in Dover Street, in the most lavish way, employing many leading craftsmen and artists of the day, including John Cobb, Vile & Cobb, John Linnell and Pierre Langlois as cabinet-makers.

Many of the pieces supplied to the 2nd Earl were still in the collection almost two centuries later, when lack of heirs and crippling death duties meant that the house and its contents had to be sold.

The house, once one of the jewels of southeast England, was partially demolished in 1959, and today is a mere shadow of its former glory.

Literature:

Illustrated:

H. Avray Tipping, ‘Ashburnham Place I’, Country Life, 22 January 1916, p. 115, illus 5 & 6.

Christopher Hussey, ‘Ashburnham Place, Sussex’, Country Life, 23 April 1953, p. 1247, illus 3 & 4.

Sotheby's, ‘Ashburnham Collections, part II, Important French and English Furniture’, sale catalogue, 26 June 1953, pl. XVII, lot 123.

David Linley, Charles Cator and Helen Chislett, Star Pieces - The Enduring Beauty of Spectacular Furniture, 2009, p. 94.

Ronald Phillips, Fine Antique English Furniture, London 2019, pp. 20-25.

-

Provenance

John, 2nd Earl Ashburnham (1724-1812), either for Ashburnham Place, Sussex, England, or Ashburnham House, Dover Street, London, England.

By descent until 1953.

Mallett & Son Ltd., London, England, 1953.

Private collection, England, formed under the guidance of R. W. Symonds, until sold anonymously in 1995.

Sir J. Paul Getty, KBE, London, England, until 2009;

Private collection, England.

Looking for something similar? YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

YOU HAVE RECENTLY VIEWED ITEMS

Make an enquiry

- CAN WE HELP YOU?

- +44 (0)20 7493 2341

- [email protected]